Ryukyu Kobudo

Consisting of a number of islands, Okinawa Prefecture is graced not only by its natural beauty but also by a unique history and distinctive culture. In the 12th century, regional lords called aji (anji) emerged and exerted power from their fortified manors called gusuku. Soon power was divided among three small kingdoms. In 1429, Sho Hashi united the island and founded the Kingdom of the Ryukyus. During the 14th to 16th centuries, a period known as the "Golden Age of Trade," the Kingdom flourished as a trade carrier for China and other nations. In 1477, the new King of Okinawa, Sho Shin, was responsible for putting a stop to feudalism on Okinawa by making all the aji (anji) move to the capital of Shuri and imposing a ban on all weapons. Developing out of necessity and opportunity, the Okinawans honed their empty hand fighting system (Te). When the Shimazu Clan from Satsuma invaded Okinawa in 1609, they continued to enforce the weapons ban and many prior Okinawan nobles (trained in empty hand and weapons systems) were forced to practice and pass on their arts in secrecy. Many of these individuals were pushed to the villages, finding a ready supply of training acolytes. Although much has been written about Okinawa's traditional Kobudo system having emerged from farming instruments as a means of self-defense from roving Samurai, this is likely a romanticized version of the truth. In one form or the other, all of Okinawan Kobudo's traditional weaponry were inexistence at this time. As with it's empty hand forms, techniques of Chinese and Southeast Asian martial arts were incorporated into Okinawan Kobudo as well. It should be noted that traditional Okinawan martial arts incorporate weapons as an integral part of karate practice, although more modern schools have emerged that appear to separate the two as distinct forms of martial practice.

Today in Okinawa, there are at least four primary kobudo ryu-ha (style) that are practiced. There is Yabiku Moden / Taira Shinken ryu-ha carried on by Akamine, Eiiryo. Yamane-ryu-ha which was established by Yamane Mansanru Chinen carried on by Kishoba. The Motobu-ryu bujutsu handed down by the Motobu family carried on by Uehara, Seikichi. The fourth ryu-ha is known as the Matayoshi ryu-ha kobudo, as taught by Odo, Seikichi. Strictly translated, the Japanese word kobudo covers all ancient martial traditions, armed or unarmed, of Okinawa or Japan. Today, when specifically referring to Okinawan traditions, the term kobudo is most often used to describe the weapons traditions of the Ryukyu Islands.

These weapons include: The bo (staff), sai (iron truncheon), nunchaku (horse bridle), kama (sickle), tekko (metal knuckles), tsuifa (millstone handle), eiku (oar), suruchin (weighted rope), and the timbi (shield and short spear).

Today in Okinawa, there are at least four primary kobudo ryu-ha (style) that are practiced. There is Yabiku Moden / Taira Shinken ryu-ha carried on by Akamine, Eiiryo. Yamane-ryu-ha which was established by Yamane Mansanru Chinen carried on by Kishoba. The Motobu-ryu bujutsu handed down by the Motobu family carried on by Uehara, Seikichi. The fourth ryu-ha is known as the Matayoshi ryu-ha kobudo, as taught by Odo, Seikichi. Strictly translated, the Japanese word kobudo covers all ancient martial traditions, armed or unarmed, of Okinawa or Japan. Today, when specifically referring to Okinawan traditions, the term kobudo is most often used to describe the weapons traditions of the Ryukyu Islands.

These weapons include: The bo (staff), sai (iron truncheon), nunchaku (horse bridle), kama (sickle), tekko (metal knuckles), tsuifa (millstone handle), eiku (oar), suruchin (weighted rope), and the timbi (shield and short spear).

MATSU, Higa (1790 – 1870) was a kobudo expert and guard for the King of Okinawa (thus carrying the title of Peichin). His expertise was in bojutsu, saijutsu, and tonfajutsu. His most notable student was Ufuchiku Kanakushiku.

UFUCHIKU, Kanakushiku (1841 – 1926) also known as Kinjo Sanda, developed Ufuchiku Kobujutsu. He was the police commissioner of Shuri who committed hara kiri on October 13, 1926. His most notable students were Shosei Kina (Menkyo Kaiden) and Saburo Takahashi.

SHOSEI, Kina (1883 – 1980), was born in the village of Shimabuku. He initially trained in Shuri-Te under Itosu, Anko and later Yabu, Kentsu. Kina then moved to kobudo training under Kanakushiku in Ufuchiku Kobujutsu. He was the heir to this system and passed on his position at his death to Kaisho Isa.

Yamane Ryu Kobudo

The origin of Yamane-ryu kobudo remains unclear. Its history can at least in part be traced back to Chinen Pechin (1846-1928). Chinen Sanda, born in the village of Samukawa (Shuri, Okinawa) was from a Pechin class. Known also as Chinen Pechin, or Yamane no Chinen, as he was described by Taira Shinken, was educated in Uchinadi by his uncle, Chinen Sanjin Andaya Pechin (1797-1881) - known as Aburaiya Yamagusuku. Although he was exposed to a number of different bojutsu, Chinen favored Sakugawa and Shikiyanaka systems.

When he passed at the age of 82, he left his kobudo traditions to a number of senior students including: Yabiku Moden, Higa Raisuke, Higa Seiichiro, Higa Ginsaburo, Akamine Yohei, Maeshiro Chotoku, his own grandson Masami and his most prominent disciple Oshiro (Ogusuku) Chojo.

Chinen Masami (1898-1976), Sanda’s grandson, named the system, Yamane Ryu (Yammani Ryu).

When he passed at the age of 82, he left his kobudo traditions to a number of senior students including: Yabiku Moden, Higa Raisuke, Higa Seiichiro, Higa Ginsaburo, Akamine Yohei, Maeshiro Chotoku, his own grandson Masami and his most prominent disciple Oshiro (Ogusuku) Chojo.

Chinen Masami (1898-1976), Sanda’s grandson, named the system, Yamane Ryu (Yammani Ryu).

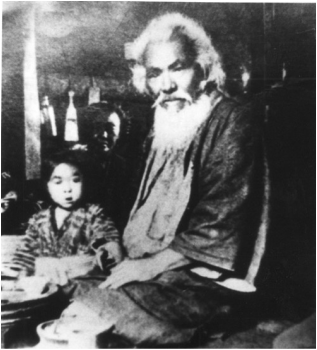

CHINEN, Sanda and his grandson, CHINEN, “Yamani” Masaru, were experts in kobudo having trained in Ufuchiku Kobujutsu. One of his most notable students was Moden Yabiku who instructed Taira Shinken. Shorinryu Shorinkan Judan, Nakazato Shugoro remains one of only a handful of living Yamani ryu teachers.

OSHIRO, Chodo (1887 – 1935), was a kobudo expert having trained under Masaru “Yamani” Chinen. His specialty, and what he is most remembered for, was his abilities with the bo.

MAESHIRO, Chotoku (1909 – 1979), was a student of Oshiro’s and an expert in Yamani-Ryu. He was known for his skill with both the sai and the bo. Unfortunately, he never accepted any students and did not pass on his teachers art.

MAESHIRO, Chotoku (1909 – 1979), was a student of Oshiro’s and an expert in Yamani-Ryu. He was known for his skill with both the sai and the bo. Unfortunately, he never accepted any students and did not pass on his teachers art.

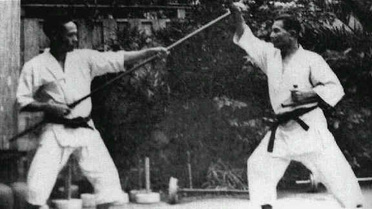

YABIKU, Moden (1878/82 – 1941/45), is known as the first Okinawan kobudo master to teach the Japanese his art form. He was trained by Chinen in Ufuchiku Kobujutsu. His most famous students were Taira Shinken and the founder of Isshin-Ryu, Tatsuo Shimabuku. He is also remembered for opening the Ryukyu Kobujutsu Kenkyu Kai.

Yabiku Moden was born in Shuri and was the eldest son of four children. His father, Yabiku Mayo, was a strict but fair man who demanded much from his children. Because Yabiku was such a frail and skinny boy in his youth, he was nicknamed "scarecrow" and was often teased and bullied by other children. Like many of his contemporaries, Yabiku Moden resolved to make his body and mind strong and as a result began the study of karatedo under Itosu Sensei and Ryukyu kobudo under various teachers including Tawata, Pechin Sensei and Chinen, Sanda (Nakamoto, 1983; Alexander, 1991; Bishop, 1996) After graduating from the Okinawa Prefectural teachers College, he taught at Bito elementary school.

He had excelled in his karatedo and kobudo training and began to teach both to the local people of Bito. Around 1911, after moving to the Japanese mainland in search of better work, Yabiku founded the Ryukyu Kobujutsu Kenkyu Kai (Ryukyu Kobujutsu Research Association) in order to promote and popularize kobudo throughout Japan (Nakamoto, 1983; Bishop, 1996).

Besides his talent in karatedo and kobudo, Yabiku was known as a master storyteller and would engage his students with stories of the old Okinawan Bushi of a by-gone era. In his daily life it was said that Yabiku was constantly challenging himself through the study of Budo by always trying to overcome his physical and mental limitations. He is known, for example, to have worn iron geta (clogs) from morning to night in order to strengthen his legs and hips. To strengthen his arms and hands, he would grasp the frame of the ceiling of his home and travel around its perimeter using only his arms. On a personal level, Yabiku was said to have been a deeply religious man who did not drink alcohol or smoke and was never heard to say a bad word against anyone (Nakamoto, 1983). Yabiku died on June 23, 1941 at the age of 63.

Yabiku Moden was born in Shuri and was the eldest son of four children. His father, Yabiku Mayo, was a strict but fair man who demanded much from his children. Because Yabiku was such a frail and skinny boy in his youth, he was nicknamed "scarecrow" and was often teased and bullied by other children. Like many of his contemporaries, Yabiku Moden resolved to make his body and mind strong and as a result began the study of karatedo under Itosu Sensei and Ryukyu kobudo under various teachers including Tawata, Pechin Sensei and Chinen, Sanda (Nakamoto, 1983; Alexander, 1991; Bishop, 1996) After graduating from the Okinawa Prefectural teachers College, he taught at Bito elementary school.

He had excelled in his karatedo and kobudo training and began to teach both to the local people of Bito. Around 1911, after moving to the Japanese mainland in search of better work, Yabiku founded the Ryukyu Kobujutsu Kenkyu Kai (Ryukyu Kobujutsu Research Association) in order to promote and popularize kobudo throughout Japan (Nakamoto, 1983; Bishop, 1996).

Besides his talent in karatedo and kobudo, Yabiku was known as a master storyteller and would engage his students with stories of the old Okinawan Bushi of a by-gone era. In his daily life it was said that Yabiku was constantly challenging himself through the study of Budo by always trying to overcome his physical and mental limitations. He is known, for example, to have worn iron geta (clogs) from morning to night in order to strengthen his legs and hips. To strengthen his arms and hands, he would grasp the frame of the ceiling of his home and travel around its perimeter using only his arms. On a personal level, Yabiku was said to have been a deeply religious man who did not drink alcohol or smoke and was never heard to say a bad word against anyone (Nakamoto, 1983). Yabiku died on June 23, 1941 at the age of 63.

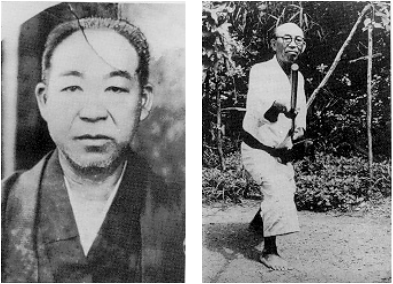

SHINKEN, Taira (1897 –1970), was born in Nakazato village on Kumejima (a Ryukyu island 135 miles from Okinawa). Taira Shinken left Okinawa for Tokyo in 1922. While there he learned karate from Funakosh, Gichin (Shotokan) and kobudo from Yabiku Moden. In 1942, he returned to the Ryukyu Islands and studied the various Ryukyuan weapons techniques and forms. In 1945, Taira began teaching kobudo in various dojo across Okinawa.

About this time, he also formed the Ryukyu Kobudo Kenkyukai, (The Society for the Research of the Ancient Martial Ways of the Ryukyu Islands) to carry on the teachings of Moden Yabiku and other teachers who had since passed away. During these early days, he researched and developed thirty kata while devising a solid, comprehensive curriculum that would become the foundation of the dojo he opened in 1959 in Naha Shi.

In 1964, he published Ryukyu Kobudo Taikan (The Encyclopedia of Ryukyu Kobudo); the first comprehensive book about Ryukyu Kobudo written in Japanese. Recently, an English translation of this seminal text became available to the public.

In failing health in 1970, Taira changed the name of his organization to Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinkokai, awarded Akamine Eisuke his Shihan (teacher's license) certificate and appointed him the second president of the organization, in essence his successor. Shinken trained many notable karateka, not least was Tatsuo Shimabuku, the founder of Isshin Ryu. Later that year, about fifty of his students were at his bedside when, at the age of seventy-three, Taira Shinken died of cancer.

About this time, he also formed the Ryukyu Kobudo Kenkyukai, (The Society for the Research of the Ancient Martial Ways of the Ryukyu Islands) to carry on the teachings of Moden Yabiku and other teachers who had since passed away. During these early days, he researched and developed thirty kata while devising a solid, comprehensive curriculum that would become the foundation of the dojo he opened in 1959 in Naha Shi.

In 1964, he published Ryukyu Kobudo Taikan (The Encyclopedia of Ryukyu Kobudo); the first comprehensive book about Ryukyu Kobudo written in Japanese. Recently, an English translation of this seminal text became available to the public.

In failing health in 1970, Taira changed the name of his organization to Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinkokai, awarded Akamine Eisuke his Shihan (teacher's license) certificate and appointed him the second president of the organization, in essence his successor. Shinken trained many notable karateka, not least was Tatsuo Shimabuku, the founder of Isshin Ryu. Later that year, about fifty of his students were at his bedside when, at the age of seventy-three, Taira Shinken died of cancer.

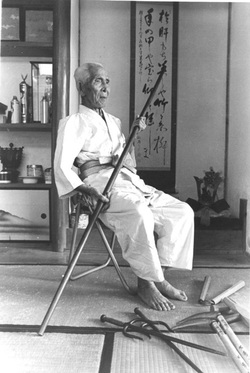

Akamine Eisuke (1925 – 1999)

Akamine Eisuke was born May 1, 1925 in the last years of the Taisho Era. Until his death on January 13, 1999, he lived in the Nesabu section of Tomigusuku, the small village in southern Okinawa where he was born.

In 1942, at the age of seventeen, he began the study of Yamani-ryu bojutsu under Higa Seichiro, Higa Raisuke, Higa Jisanburo and Akamine Yohei (no relation). From his early teachers, Akamine learned the following kata: Soeshi no Kon, Sakugawa no Kon, Shirataru no Kon and Yuniga no Kon. In 1944, Akamine married Shizuko and soon after, at age nineteen, he was drafted into the Japanese army where he served one year in Taiwan. When he returned to Okinawa, Akamine resumed vegetable and sugar cane farming and his study of Yamani-ryu bojutsu.

In 1959, Taira Shinken was teaching kobudo in a Goju-ryu karate dojo in Naha, Okinawa. While there, he heard of great bojutsu teachers who lived in the Kakazu section of Tomigusuku village. To satisfy his curiosity, he went to Tomigusuku to study Yamani-ryu bojutsu with Akamine's teachers. This was the first meeting between Taira Shinken and Akamine.

As history tells it, one day Taira was asked to demonstrate tekko (metal knuckles), nunchaku (horse bridle) and sai (truncheon). Akamine had never seen these weapons before. He was so impressed with Taira's waza that he decided to become his deshi (student). As Taira's senior student, Akamine would be in the unique position of watching him organize the various waza into a system that would eventually become the Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinkokai.

Akamine Eisuke was born May 1, 1925 in the last years of the Taisho Era. Until his death on January 13, 1999, he lived in the Nesabu section of Tomigusuku, the small village in southern Okinawa where he was born.

In 1942, at the age of seventeen, he began the study of Yamani-ryu bojutsu under Higa Seichiro, Higa Raisuke, Higa Jisanburo and Akamine Yohei (no relation). From his early teachers, Akamine learned the following kata: Soeshi no Kon, Sakugawa no Kon, Shirataru no Kon and Yuniga no Kon. In 1944, Akamine married Shizuko and soon after, at age nineteen, he was drafted into the Japanese army where he served one year in Taiwan. When he returned to Okinawa, Akamine resumed vegetable and sugar cane farming and his study of Yamani-ryu bojutsu.

In 1959, Taira Shinken was teaching kobudo in a Goju-ryu karate dojo in Naha, Okinawa. While there, he heard of great bojutsu teachers who lived in the Kakazu section of Tomigusuku village. To satisfy his curiosity, he went to Tomigusuku to study Yamani-ryu bojutsu with Akamine's teachers. This was the first meeting between Taira Shinken and Akamine.

As history tells it, one day Taira was asked to demonstrate tekko (metal knuckles), nunchaku (horse bridle) and sai (truncheon). Akamine had never seen these weapons before. He was so impressed with Taira's waza that he decided to become his deshi (student). As Taira's senior student, Akamine would be in the unique position of watching him organize the various waza into a system that would eventually become the Ryukyu Kobudo Hozon Shinkokai.

Matayoshi Kobudo

Matayoshi Shinko was born in Naha, Okinawa in 1988. He left Okinawa at the age of 22 in order to study various weapon systems in Asia. In 1915, during Funakoshi’s demonstration of karate at the Budo Festival in Tokyo, Shinko demonstrated kobudo. Shinko’s son, Matayoshi Shinpo was introduced to kobudo by his father in 1927 at the age of 6. Shinko returned to Okinawa in 1935 and settled back in Naha. At the age of 59 (1947) Shinko passed away. Prior to this time, Shinpo was training and teaching Kingai Ryu and Kawasaki-Shi. Upon the death of his father, Shinpo returned to Okinawa in order to teach kobudo and in 1960 he formed the Ryukyu Kobudo Association. He renamed his association the Zen Okinawa Renmei in 1972. In 1997, at the age of 76, Matayoshi Shinpo passed away and left his system to his son, Matayoshi Yasushi (b. 1965).

Nakaima Kobudo

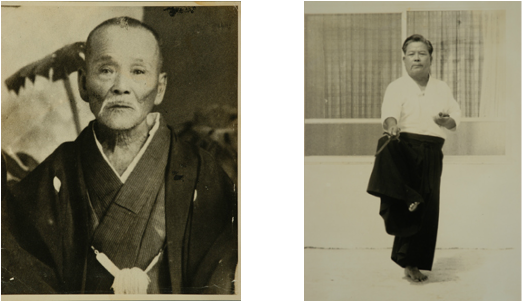

The originator of the Ryueiryu method was the Okinawan Nakaima Norisato (also known as Kenri). Born December, 1819 into a wealthy family, he developed a passion for the martial arts at a young age, and was known throughout the village of Kumemura (Kume) for his devotion to cultural and combative arts.

The area called Kume in Naha was settled by Chinese (often referred to as the "Thirty-six family names") from Fukien (Fukuken, Fukuken-sho), China about 600 years ago. Being born and brought up in the area under deep influence from China, Norisato was very familiar with Chinese cultural ways and could speak and communicate freely in at least one dialect of the language. As history tells, during a visit by Chinese ambassadors (a practice continued until 1866), Norisato’s interest in the martial arts became known and with the help of a Chinese military envoy to Okinawa, he was provided a letter of introduction and sent to China to study the martial arts. At the age of nineteen, Nakaima was accepted as a disciple of the Chinese Master Ru Ru Ko, who at the time was the lead instructor at the Military Academy in Beijing.

After seven years of diligent study under the master, Nakaima graduated and was awarded his masters teaching degree at the age of 26. Reportedly, at this time he was given secret texts detailing information about the combative traditions of China. Included in this group from his teacher was the "Bubishi" and other books regarding strategy and fighting systems. Before he returned to his homeland, Nakaima traveled throughout the Fukien, Canton and Beijing areas of China. There he saw many unique methods of training and embraced many teachings. Additionally, he collected many weapons from the various areas he visited and incorporated them into his personal system of Chinese boxing.

The system that Nakaima had learned and devised was taught only to his son, Noritada Kenchu (1856–1953). In turn, Noritada only taught his own son Noritaka (Kenko) and grandchildren, who also took the family oath of secrecy. While Nakaima Noritada (Kenchu) had no other students, he was regarded as a master of martial arts by his contemporaries.

Nakaima Noritaka was the first family member to break the family tradition and at the age of 60, fearing that the family art would be lost, accepted a small group of outside students. These students, all school teachers, Nakaima felt possessed the necessary character, education and background to continue the teachings in the proper manner.

Nakaima Kenko was a well-respected leader in the Okinawan martial arts community and was a key figure in the growth of several organized movements of the late 1950s through the 1960s. He remained an important figure in the development of martial arts on Okinawa until his death in 1989. The current leader of the system is Nakaima Kenji, the 5th generation Soke of the family art.

The area called Kume in Naha was settled by Chinese (often referred to as the "Thirty-six family names") from Fukien (Fukuken, Fukuken-sho), China about 600 years ago. Being born and brought up in the area under deep influence from China, Norisato was very familiar with Chinese cultural ways and could speak and communicate freely in at least one dialect of the language. As history tells, during a visit by Chinese ambassadors (a practice continued until 1866), Norisato’s interest in the martial arts became known and with the help of a Chinese military envoy to Okinawa, he was provided a letter of introduction and sent to China to study the martial arts. At the age of nineteen, Nakaima was accepted as a disciple of the Chinese Master Ru Ru Ko, who at the time was the lead instructor at the Military Academy in Beijing.

After seven years of diligent study under the master, Nakaima graduated and was awarded his masters teaching degree at the age of 26. Reportedly, at this time he was given secret texts detailing information about the combative traditions of China. Included in this group from his teacher was the "Bubishi" and other books regarding strategy and fighting systems. Before he returned to his homeland, Nakaima traveled throughout the Fukien, Canton and Beijing areas of China. There he saw many unique methods of training and embraced many teachings. Additionally, he collected many weapons from the various areas he visited and incorporated them into his personal system of Chinese boxing.

The system that Nakaima had learned and devised was taught only to his son, Noritada Kenchu (1856–1953). In turn, Noritada only taught his own son Noritaka (Kenko) and grandchildren, who also took the family oath of secrecy. While Nakaima Noritada (Kenchu) had no other students, he was regarded as a master of martial arts by his contemporaries.

Nakaima Noritaka was the first family member to break the family tradition and at the age of 60, fearing that the family art would be lost, accepted a small group of outside students. These students, all school teachers, Nakaima felt possessed the necessary character, education and background to continue the teachings in the proper manner.

Nakaima Kenko was a well-respected leader in the Okinawan martial arts community and was a key figure in the growth of several organized movements of the late 1950s through the 1960s. He remained an important figure in the development of martial arts on Okinawa until his death in 1989. The current leader of the system is Nakaima Kenji, the 5th generation Soke of the family art.

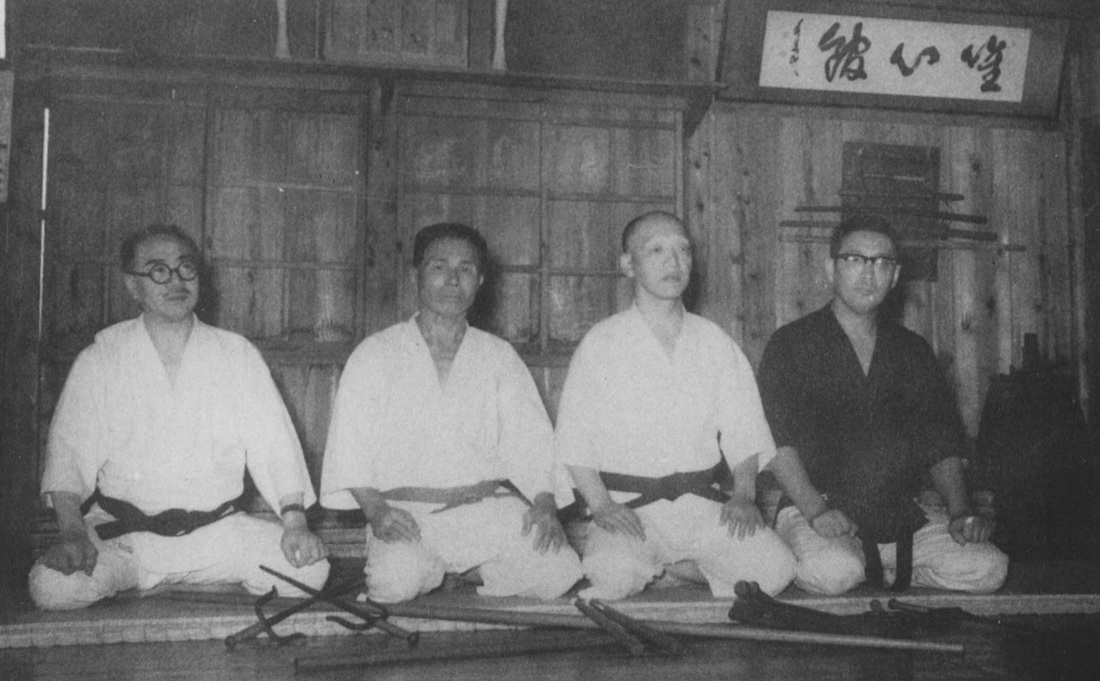

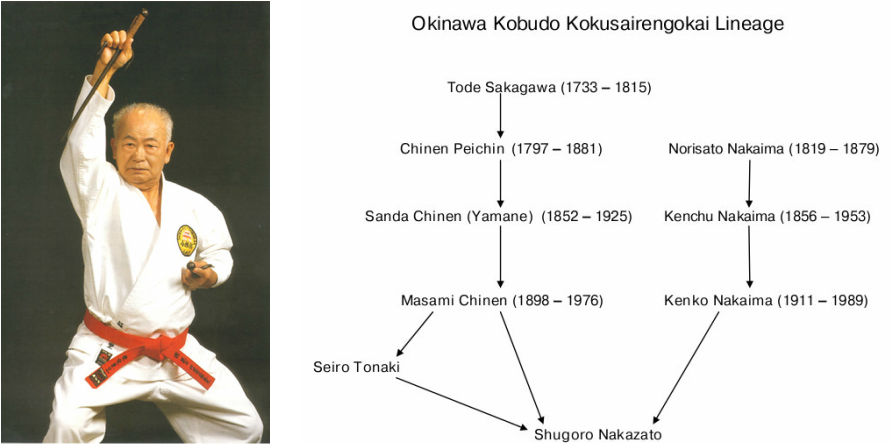

Shorin Ryu Shorinkan Kobudo

The kobudo tradition taught by Hanshi Shugoro Nakazato of Shoinkan is called, “Okinawa Kobudo Kokusaireingokai”. Nakazato began his training in both Karate and Kobudo in 1935. Prior to WWII he trained under Seiro Tonaki. After the war, Nakazato trained under Tonaki's teacher Masami Chinen. Both of Nakazato's teachers had been students of Sanda Chinen (Yamani). After Sanda Chinen's death, Masami Chinen named his style Yamani Ryu in honor of his father. Sanda Chinen learned Bo-Jitsu from his father, Chinen Peichin. Chinen Peichin was a student of Tode Sakagawa.

In addition, a parallel line in Nakazato's kobudo lineage comes from Kenko Nakaima who, in 1960, named his family's fighting style Ryuei Ryu and began training non-family members. The Nakaima family lineage goes back through Kenko's father, Kenchu and his father, Norisato Nakaima who studied martial arts during his stay in China. For a greater discussion of the Nakaima system see above.

In addition, a parallel line in Nakazato's kobudo lineage comes from Kenko Nakaima who, in 1960, named his family's fighting style Ryuei Ryu and began training non-family members. The Nakaima family lineage goes back through Kenko's father, Kenchu and his father, Norisato Nakaima who studied martial arts during his stay in China. For a greater discussion of the Nakaima system see above.

Traditional Weapons of Okinawa

Bo (boh) also known as a Kon by Okinawan practitioners

The word “rokushakubo” means 6 foot staff. Roku is 6, Shaku is a measurement approximately 1 foot, and Bo is staff. It is made from hardwood. The Bo is approximately 6 feet in length, in principle the Bo should be at least one fist length taller than the wielder. Its diameter is between 1 and 2 inches. The Bo can be straight or tapering towards the ends.

The bo was derived from a farming tool called a tenbib (tin-beeb), which was used to carry buckets or bundles around on either end. This tool came in a variety of shapes and sizes. The most common was the rokushakumarubo (roh-ku-shah-ku-mah-ruh-boh), which is a six foot piece of round wood. Other shapes included kaku bo (four sided bo), rokaku bo (six sided bo) and hakkaku bo (eight sided bo). The Okinawan bo is tapered at both ends rather than one diameter. This is a full range weapon that can also be used in thirds. When gripping the bo there are two hand positions used: Honte mochi (hon-teh moh-chee) the natural grip where palms oppose one another and gyaku mochi (gah-koo moh-chee) where the palms face the same directions. When striking, the end of the bo that is closest to the body will be placed on the outside of the lower part of the forearm. The bo employs various blocks and strikes. It is typically the most widely used weapon.

The Bo depends entirely on Te (hand) techniques. Proper turning and twisting of the wrist is necessary. In the past, kobudo masters spent many years practicing with the Bo before attempting combat. The power is generated by the back hand pulling the Bo. The front hand is used for guidance. It is important to twist the wrist when striking and poking just like turning the hand over when punching.

Sai (sigh)

The three pronged, metal truncheon is a unique weapon believed to have been introduced to Okinawa by the Chinese in and around the late 1400's. The sai was employed by the local law enforcement the same way the modern day police use their night stick. There has been some controversy and even some speculation as to the origin of the sai. Some believe it to be a weapon that was created as opposed to a farming or fishing tool, similar to a tool used in China to create holes in the ground for seeds. Some even believe that the sai were at one time a bladed weapon. Regardless, as previously stated, it was in existence as a martial tool prior to the weapons bans of the 15th and 16th centuries.

It is a hand weapon with a blade between 15 and 20 inches in length with forward curving quillions, hand grip, and pommel. It is made from solid iron weighing up to 3 pounds. By gripping them with either the honte mochi and gyaku mochi, the practitioner can manipulate the sai with deadly speed and accuracy. With the sai, the shaft is referred to as the monouchi (moh-noh-oo-chee), the tip is the saki (sah-kee), and the bottom rounded part of the handle is the tsukagushira (tsue-kah-ghoo-she-rah). A quarter way up the shaft are two curved prongs called the yoku (yoh-kuh) and the tip of the prongs are called tsume (tsue-meh). The size of the sai depend on the individual using them. The monouchi should cover the forearm with the saki extending at least one inch past the elbow. The size of the yoku are important also; because of the grappling and catching abilities of the sai the distances between the monouchi and the yoku should be narrow. The sai employs striking, blocking, punching, cutting, and stabbing capabilities.

Often 2 or 3 Sai were carried, 1 in each hand and a third in his belt in reserve. The Sai is restricted to Okinawan-based Karate systems. The use of the Sai requires a very high standard of training and skill. Each Sai must function in harmony with the other. Proper use of the Sai requires many years of training. The Sai has several grips. An open Sai is when the Tsukagashira is at the heal of the palm. A closed Sai is when the Tsukagashira is at the finger tips and the Monouchi lies on the forearm. The Yoko is used for trapping and breaking of weapons.

Tonfa/Tunfa (toon-fah)

The Tunfa is made of hardwood. It is between 15 to 20 inches in length with a projecting side handle about 6 inches down the from the front end. The Ushiro Tsukagashira should extend 1 to 3 inches past the elbow. The body of the Tunfa may be square or round. Traditionally, it has been suggested that the Tunfa was used as a handle to turn a hand operated millstone when grinding rice or a crank handle for drawing water from a well. However, a very similar weapon exists among Chinese martial arts and it is more likely that the Tunfa of Okinawa finds its origin from an adaptation of this weapon. Like the Sai, the Tunfa is typically used in pairs (but can be an effective weapon used singularly). Used singularly or in pairs, the practitioner could defend against other weapons effectively, such as a katana or bo. The Tunfa employs striking, blocking, and punching as it's techniques. The handle allows the user to swing the Tunfa outward for striking and blocking while letting it return to the outside of the forearm to prepare for the next technique.

The Tunfa is gripped so that the thumb and index finger are at the Tsuka and the Yoko Nage is on the bottom of the forearm. It can be used for punching and blocking as in karate. The true power of the Tunfa comes from the swinging motions used for striking and blocking. The Tunfa takes time to develop smooth techniques. Each Tunfa must work in harmony with the other. Proper spinning, rotation, and control require many hours of practice.

Nunchaku (noon-chah-kuh)

One of the most popular martial arts weapons, tradition points to one of two origins for the nunchaku. The first of which is an old style horse's bit and bridle called a muge (moo-geh), and the second (and less likely origin) is a flail used to pound grain or rice. Nunchaku come in different shapes and sizes. In Mateyoshi tyr-ha, the most common types of nunchaku are the hakkakukei (hahk-kah-ku-kheh), which are octagonal shaped and maru-gata (mah-rue-gah-tah), which is round. Both are connected by three lengths of cord about three finger widths wide. Sometimes the nunchaku can be connected by a piece of vine called kanda (kahn-dah). The kanda was usually longer than the cord due to the fact that this type of connector could bind an adversaries' hands and head. The nunchaku are capable of blocking and striking, as well as trapping and throwing. The motions are not like those seen in movies but are more similar to the movements of the other weapons, like the bo or katana.

The Nuchaku is gripped at the Ushiro Tsukagashira. It is first whirled in a fast figure-eight or zigzag motion before the opponent with the object of disturbing the composure and gaining a mental initiative. The rotating of the Nunchaku comes from the wrist motion. As the Nunchaku rotates, the two pieces of wood should stay in line with each other. The free hand caries out the normal Te movements of blocking and defending and as the chances occur. The Nunchaku delivers smashing blows to the face, hands, wrists, knees, shoulder blades, or the ribs.

Kama (kah-mah)

The Kama has a short blade at right angles to a hardwood handle. The handle is a little longer than your forearm and tapers from the Gedan Tsukagashir to the Ushiro Tsukagashira. The Monouchi is between 6 and 10 inches in length. It is sometimes upgraded to Kama-Yari (Spear with a hook blade) and the Kusari-Gama (Sickle and Chain).

The Kama is a hand-held sickle that likely had many utilitarian uses, rice harvesting being one among them. It can be found in Southern Asia and Japan. The weapon is usually referred to as ni-cho kama (nee-choh kah-mah), which translates into a "pair of kama" used in a combative manner. The blades can be used, of course, to cut with, the back of the blade can be used like a club to strike with, and the handle can be used to block and punch with. Typically two Kama are used. Because of the Monouchi and the difficult techniques used, the Kama is considered an advance weapon.

The Kama is gripped at the Ushiro Tsukagashira not at the Moto. The Kama has two positions, open and closed. The open position is when the Kama is gripped like a hammer. The closed position is when the handle of the Kama rests along the forearm. The Kama rotates between the index finger and the thumb when going from the open and closed positions. Great care and focus is required as well as many hours of practice.

Eku/Eaku/Eiku (eeh-kuu)

Used originally as a boat oar, the eku is capable of being used similarly to that of the bo. The Eku is made from hardwood. It is shorter than the Bo. In principle the Eku is the same height as the wielder. The Monouchi extends one-third the length of the Eku. \The Monouchi has 4 surfaces, the Saki, 2 Yoko, a beveled edge, and a rounded face. The Eku is uniquely Okinawan. The Eku was a common place oar put to deadly use by the Okinawan fishermen. The Eku uses the techniques of the Bo. However, the Eku requires more skill because of the necessary wrist action needed to use the proper surface. Use of the Eku requires excellent knowledge of Bo techniques.

The grips for the Eku are similar to the ones for the Bo. The right hand grips the Eku at the Moto right behind the Monouchi. The left hand is about one shoulder width down from the right hand. Like the Bo the back hand generates the power and the front hand is used for guidance and control. One of the techniques employed while using the eku, is taking the wide, flat part of the weapon and throwing sand in your opponent's face.

Tekko (teh-koh)

This weapon has two possible origins. One lies in the idea that the tekko was used on board fishing boats while pulling the net in so the net would not cut into the hand. The other was the use of a horse shoe simply put into the hand and used to punch with. The first one was made out of wood while the other was made, of course, out of metal. These weapons employ blocking, striking, grabbing, and joint locking.

Nunti-bo (noon-teh boh)

Some say that this weapon came from China while others say it was a tool used on the fishing boats to bring in the nets. It consists of a six foot bo with a nunti sai mounted on top. Used like a bo, the nunti-bo can strike, block, grab, and puncture.

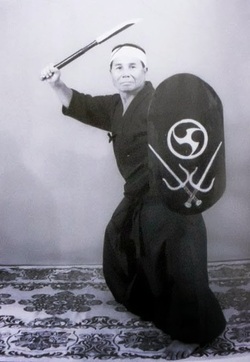

Tinbe / Rochin (ten-bay / roh-chen)

The rochin is a twelve to eighteen inch piece of wood with a three to four inch blade on the end. The rochin is used in conjunction with the tinbe, a type of shield usually made out of a turtle shell. As one can guess, the shield is used for deflecting incoming attacks while the rochin would be used to strike back.

Other weapons used on Okinawa are: the kuwa (Okinawan hoe), suruchin (a long chain, weighted at both ends), the abumi (a wooden saddle stirrup), naginata (a seven foot bo with a curved blade on the end), yari (spear), and of course, the katana (a single edged, curved sword).

The word “rokushakubo” means 6 foot staff. Roku is 6, Shaku is a measurement approximately 1 foot, and Bo is staff. It is made from hardwood. The Bo is approximately 6 feet in length, in principle the Bo should be at least one fist length taller than the wielder. Its diameter is between 1 and 2 inches. The Bo can be straight or tapering towards the ends.

The bo was derived from a farming tool called a tenbib (tin-beeb), which was used to carry buckets or bundles around on either end. This tool came in a variety of shapes and sizes. The most common was the rokushakumarubo (roh-ku-shah-ku-mah-ruh-boh), which is a six foot piece of round wood. Other shapes included kaku bo (four sided bo), rokaku bo (six sided bo) and hakkaku bo (eight sided bo). The Okinawan bo is tapered at both ends rather than one diameter. This is a full range weapon that can also be used in thirds. When gripping the bo there are two hand positions used: Honte mochi (hon-teh moh-chee) the natural grip where palms oppose one another and gyaku mochi (gah-koo moh-chee) where the palms face the same directions. When striking, the end of the bo that is closest to the body will be placed on the outside of the lower part of the forearm. The bo employs various blocks and strikes. It is typically the most widely used weapon.

The Bo depends entirely on Te (hand) techniques. Proper turning and twisting of the wrist is necessary. In the past, kobudo masters spent many years practicing with the Bo before attempting combat. The power is generated by the back hand pulling the Bo. The front hand is used for guidance. It is important to twist the wrist when striking and poking just like turning the hand over when punching.

Sai (sigh)

The three pronged, metal truncheon is a unique weapon believed to have been introduced to Okinawa by the Chinese in and around the late 1400's. The sai was employed by the local law enforcement the same way the modern day police use their night stick. There has been some controversy and even some speculation as to the origin of the sai. Some believe it to be a weapon that was created as opposed to a farming or fishing tool, similar to a tool used in China to create holes in the ground for seeds. Some even believe that the sai were at one time a bladed weapon. Regardless, as previously stated, it was in existence as a martial tool prior to the weapons bans of the 15th and 16th centuries.

It is a hand weapon with a blade between 15 and 20 inches in length with forward curving quillions, hand grip, and pommel. It is made from solid iron weighing up to 3 pounds. By gripping them with either the honte mochi and gyaku mochi, the practitioner can manipulate the sai with deadly speed and accuracy. With the sai, the shaft is referred to as the monouchi (moh-noh-oo-chee), the tip is the saki (sah-kee), and the bottom rounded part of the handle is the tsukagushira (tsue-kah-ghoo-she-rah). A quarter way up the shaft are two curved prongs called the yoku (yoh-kuh) and the tip of the prongs are called tsume (tsue-meh). The size of the sai depend on the individual using them. The monouchi should cover the forearm with the saki extending at least one inch past the elbow. The size of the yoku are important also; because of the grappling and catching abilities of the sai the distances between the monouchi and the yoku should be narrow. The sai employs striking, blocking, punching, cutting, and stabbing capabilities.

Often 2 or 3 Sai were carried, 1 in each hand and a third in his belt in reserve. The Sai is restricted to Okinawan-based Karate systems. The use of the Sai requires a very high standard of training and skill. Each Sai must function in harmony with the other. Proper use of the Sai requires many years of training. The Sai has several grips. An open Sai is when the Tsukagashira is at the heal of the palm. A closed Sai is when the Tsukagashira is at the finger tips and the Monouchi lies on the forearm. The Yoko is used for trapping and breaking of weapons.

Tonfa/Tunfa (toon-fah)

The Tunfa is made of hardwood. It is between 15 to 20 inches in length with a projecting side handle about 6 inches down the from the front end. The Ushiro Tsukagashira should extend 1 to 3 inches past the elbow. The body of the Tunfa may be square or round. Traditionally, it has been suggested that the Tunfa was used as a handle to turn a hand operated millstone when grinding rice or a crank handle for drawing water from a well. However, a very similar weapon exists among Chinese martial arts and it is more likely that the Tunfa of Okinawa finds its origin from an adaptation of this weapon. Like the Sai, the Tunfa is typically used in pairs (but can be an effective weapon used singularly). Used singularly or in pairs, the practitioner could defend against other weapons effectively, such as a katana or bo. The Tunfa employs striking, blocking, and punching as it's techniques. The handle allows the user to swing the Tunfa outward for striking and blocking while letting it return to the outside of the forearm to prepare for the next technique.

The Tunfa is gripped so that the thumb and index finger are at the Tsuka and the Yoko Nage is on the bottom of the forearm. It can be used for punching and blocking as in karate. The true power of the Tunfa comes from the swinging motions used for striking and blocking. The Tunfa takes time to develop smooth techniques. Each Tunfa must work in harmony with the other. Proper spinning, rotation, and control require many hours of practice.

Nunchaku (noon-chah-kuh)

One of the most popular martial arts weapons, tradition points to one of two origins for the nunchaku. The first of which is an old style horse's bit and bridle called a muge (moo-geh), and the second (and less likely origin) is a flail used to pound grain or rice. Nunchaku come in different shapes and sizes. In Mateyoshi tyr-ha, the most common types of nunchaku are the hakkakukei (hahk-kah-ku-kheh), which are octagonal shaped and maru-gata (mah-rue-gah-tah), which is round. Both are connected by three lengths of cord about three finger widths wide. Sometimes the nunchaku can be connected by a piece of vine called kanda (kahn-dah). The kanda was usually longer than the cord due to the fact that this type of connector could bind an adversaries' hands and head. The nunchaku are capable of blocking and striking, as well as trapping and throwing. The motions are not like those seen in movies but are more similar to the movements of the other weapons, like the bo or katana.

The Nuchaku is gripped at the Ushiro Tsukagashira. It is first whirled in a fast figure-eight or zigzag motion before the opponent with the object of disturbing the composure and gaining a mental initiative. The rotating of the Nunchaku comes from the wrist motion. As the Nunchaku rotates, the two pieces of wood should stay in line with each other. The free hand caries out the normal Te movements of blocking and defending and as the chances occur. The Nunchaku delivers smashing blows to the face, hands, wrists, knees, shoulder blades, or the ribs.

Kama (kah-mah)

The Kama has a short blade at right angles to a hardwood handle. The handle is a little longer than your forearm and tapers from the Gedan Tsukagashir to the Ushiro Tsukagashira. The Monouchi is between 6 and 10 inches in length. It is sometimes upgraded to Kama-Yari (Spear with a hook blade) and the Kusari-Gama (Sickle and Chain).

The Kama is a hand-held sickle that likely had many utilitarian uses, rice harvesting being one among them. It can be found in Southern Asia and Japan. The weapon is usually referred to as ni-cho kama (nee-choh kah-mah), which translates into a "pair of kama" used in a combative manner. The blades can be used, of course, to cut with, the back of the blade can be used like a club to strike with, and the handle can be used to block and punch with. Typically two Kama are used. Because of the Monouchi and the difficult techniques used, the Kama is considered an advance weapon.

The Kama is gripped at the Ushiro Tsukagashira not at the Moto. The Kama has two positions, open and closed. The open position is when the Kama is gripped like a hammer. The closed position is when the handle of the Kama rests along the forearm. The Kama rotates between the index finger and the thumb when going from the open and closed positions. Great care and focus is required as well as many hours of practice.

Eku/Eaku/Eiku (eeh-kuu)

Used originally as a boat oar, the eku is capable of being used similarly to that of the bo. The Eku is made from hardwood. It is shorter than the Bo. In principle the Eku is the same height as the wielder. The Monouchi extends one-third the length of the Eku. \The Monouchi has 4 surfaces, the Saki, 2 Yoko, a beveled edge, and a rounded face. The Eku is uniquely Okinawan. The Eku was a common place oar put to deadly use by the Okinawan fishermen. The Eku uses the techniques of the Bo. However, the Eku requires more skill because of the necessary wrist action needed to use the proper surface. Use of the Eku requires excellent knowledge of Bo techniques.

The grips for the Eku are similar to the ones for the Bo. The right hand grips the Eku at the Moto right behind the Monouchi. The left hand is about one shoulder width down from the right hand. Like the Bo the back hand generates the power and the front hand is used for guidance and control. One of the techniques employed while using the eku, is taking the wide, flat part of the weapon and throwing sand in your opponent's face.

Tekko (teh-koh)

This weapon has two possible origins. One lies in the idea that the tekko was used on board fishing boats while pulling the net in so the net would not cut into the hand. The other was the use of a horse shoe simply put into the hand and used to punch with. The first one was made out of wood while the other was made, of course, out of metal. These weapons employ blocking, striking, grabbing, and joint locking.

Nunti-bo (noon-teh boh)

Some say that this weapon came from China while others say it was a tool used on the fishing boats to bring in the nets. It consists of a six foot bo with a nunti sai mounted on top. Used like a bo, the nunti-bo can strike, block, grab, and puncture.

Tinbe / Rochin (ten-bay / roh-chen)

The rochin is a twelve to eighteen inch piece of wood with a three to four inch blade on the end. The rochin is used in conjunction with the tinbe, a type of shield usually made out of a turtle shell. As one can guess, the shield is used for deflecting incoming attacks while the rochin would be used to strike back.

Other weapons used on Okinawa are: the kuwa (Okinawan hoe), suruchin (a long chain, weighted at both ends), the abumi (a wooden saddle stirrup), naginata (a seven foot bo with a curved blade on the end), yari (spear), and of course, the katana (a single edged, curved sword).