The following information is intended to explore the rich history of Okinawa and its unique contribution to the development of Karate and Kobudo. The information is presented in good faith, drawn from many different sources and authors, and to honor many different martial arts disciplines and traditions that claim Okinawa as their birthplace.

The History of Okinawan Karate

The Island of Okinawa

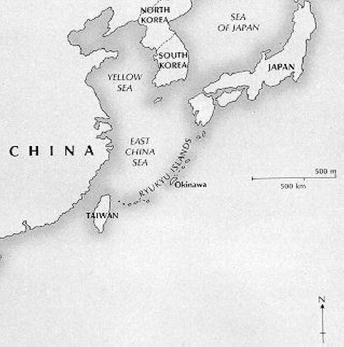

The Ryukyu archipelago is an island chain that extends from the southern tip of Japan to the island of Taiwan. Okinawa is the principal island within Ryukyu. Okinawa, meaning "rope in the offing," is an appropriate name for the island, which is a linked chain of volcanic land that looks somewhat like a rope that has been caste away into the sea.

Okinawa is approximately 6 miles wide and only about 70 miles long (a total area of approximately 460 square miles). It is situated 400 nautical miles east of mainland China, 300 nautical miles south of mainland Japan and a similar distance north of Taiwan. Being at the crossroads of major trading routes, its significance as a port of opportunity and interest was discovered early on by the Japanese. It later developed as a trade center for southeastern Asia, trading with Japan and China, as well as part of southeast Asia such as Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippine islands.

Written records of the seventh and eighth centuries in Okinawan history are filled with accounts of island warfare. At that time, Okinawa wasn't unified; instead, the island was ruled by regional chieftains. During the tenth and eleventh centuries, Japan was witness to the emergence of two powerful families, the Tairo family and the Minamoto family. As fate would have it, these two families entered into a conflict that reverberated throughout Japan and the surrounding islands. The survivors of this struggle and their knowledge of martial skills and weapons systems flooded into the Ruykyus. They brought various weapons to Okinawa as well including the katana and the tachi (swords), the yari (spear), the nanigata (halberd), and the yumi and ya (bow and arrow). The first king of Okinawa, Shunten (ca. 13th century) built various fortifications throughout the island and his successors followed suit. Over the course of the next century, Okinawa witnessed a rapid increase in formal relations with China, Korea, and Japan. Moreover, they established trade with Arabia, Java, Sumatra, and Malacca. It was inevitable that martial art traditions and practices from these countries would migrate to Okinawa as well (Hall, 1970).

Okinawa is approximately 6 miles wide and only about 70 miles long (a total area of approximately 460 square miles). It is situated 400 nautical miles east of mainland China, 300 nautical miles south of mainland Japan and a similar distance north of Taiwan. Being at the crossroads of major trading routes, its significance as a port of opportunity and interest was discovered early on by the Japanese. It later developed as a trade center for southeastern Asia, trading with Japan and China, as well as part of southeast Asia such as Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippine islands.

Written records of the seventh and eighth centuries in Okinawan history are filled with accounts of island warfare. At that time, Okinawa wasn't unified; instead, the island was ruled by regional chieftains. During the tenth and eleventh centuries, Japan was witness to the emergence of two powerful families, the Tairo family and the Minamoto family. As fate would have it, these two families entered into a conflict that reverberated throughout Japan and the surrounding islands. The survivors of this struggle and their knowledge of martial skills and weapons systems flooded into the Ruykyus. They brought various weapons to Okinawa as well including the katana and the tachi (swords), the yari (spear), the nanigata (halberd), and the yumi and ya (bow and arrow). The first king of Okinawa, Shunten (ca. 13th century) built various fortifications throughout the island and his successors followed suit. Over the course of the next century, Okinawa witnessed a rapid increase in formal relations with China, Korea, and Japan. Moreover, they established trade with Arabia, Java, Sumatra, and Malacca. It was inevitable that martial art traditions and practices from these countries would migrate to Okinawa as well (Hall, 1970).

Kumemura and Cultural Exchange

It is unknown when the first exchange of martial arts techniques and practices occurred. However, in 1392, Okinawa's King Satto exchanged diplomatic delegations with the Ming Emperor. Part of this exchange included the settlement of Chinese families as a form of cultural exchange and diplomatic representation to live among the people of Okinawa. Very little is known with certainty about this initial 36-family-transplant from Southern China (Fujian province); however, it is believed that they settled in Naha, near the Shuri capital, in a community known as Kumemura (Lewis, 1993; Nagamine, 1998).

Their presence was likely an enhancement of existing trade and exchange between the Chinese kingdom and the Ryukyuans. This unique community would later play a vital and influential role in the geopolitics between Japan and China; however, of greater interest to practitioners of karate, is the influence it had on the origins and evolution of Okinawan karate. As is well known to most karateka, before receiving the "empty hand" designation, karate on Okinawa was known as Toudi or Tode, meaning "China hand", an allusion to the influence of Chinese martial arts (and perhaps specifically the martial traditions brought by these families to Kumemura, traditions heavily influenced by Southern Chinese styles such as white crane, McCarthy, 1987).

Their presence was likely an enhancement of existing trade and exchange between the Chinese kingdom and the Ryukyuans. This unique community would later play a vital and influential role in the geopolitics between Japan and China; however, of greater interest to practitioners of karate, is the influence it had on the origins and evolution of Okinawan karate. As is well known to most karateka, before receiving the "empty hand" designation, karate on Okinawa was known as Toudi or Tode, meaning "China hand", an allusion to the influence of Chinese martial arts (and perhaps specifically the martial traditions brought by these families to Kumemura, traditions heavily influenced by Southern Chinese styles such as white crane, McCarthy, 1987).

Japan's Weapons Ban

tween 1477 and 1526 Okinawa was ruled by King Sho Shin who banned the ownership of weapons. All weapons (typically swords) were stored in a government warehouse under the direct control of the king. These sword edicts predate those issued by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in Japan (1586 and 1587) and by later edicts of Tokugawa Iemitsu. It is widely believed that the effect of these bans was to stimulate the development of empty-hand fighting methods, although it is likely that such bans included Ryukyuan nobility that had been trained in the use weapons and were already trained in Tode or Okinawan Te. In 1609, Japan's Satsuma clan came to power and continued the ban. During this period, great secrecy fell upon the arts and the various schools of fighting hid their practice, so as not to be observed by others (government officials or rival clans and families). Out of necessity, it is believed that most systems of martial training were handed down within known and trusted groups or as part of traditional privilege (royal family and nobility). While some weapons may have had occasional ceremonial use, even this expression was carefully controlled by the Japanese government.

Okinawa-Te, Toudi, and Tode

As a result of the prohibition on weapons, Chinese combat methods and existing Okinawan fighting techniques were likely studied and practiced clandestinely. Gradually, these empty-hand styles (probably forms of Chinese Kempo) took on distinct Okinawan influences after co-mingling with the indigenous martial forms previously developed on the island. These styles became known as Okinawan Te (Tode) or simply Te, meaning, "hand." This innocuous name helped to maintain the secrecy of instruction, which, according to the difference in regions and teachers, developed into several main styles.

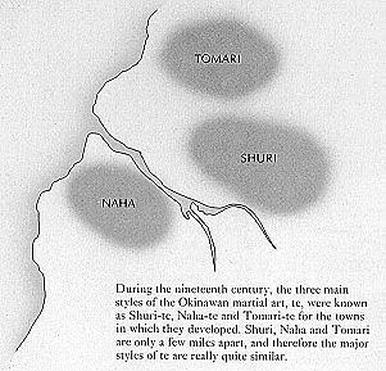

As tradition tells us, Okinawan Te continued to develop over the years, primarily in three Okinawan cities: Shuri, Naha and Tomari. Each of these towns was a center to a different sect of society: kings and nobles, merchants and business people, and farmers and fishermen, respectively. For this reason, different forms of self-defense developed within each city and subsequently became known as Shuri-Te, Naha-Te and Tomari-Te. Collectively, they constituted Okinawa-Te or Tode (also To-te). Gradually, Te was divided into two main groups: Shorin-ryu, which developed around Shuri and Tomari systems, and Shorei-ryu, which originated from the Naha area. It is important to note, however, that the towns of Shuri, Tomari, Naha are only a few miles apart, and that the differences between their arts were essentially ones of emphasis, not of kind (Bishop, 1994). Furthermore, it has been posited that early masters in these respective areas likely shared information and techniques with each other.

The differences between Shuri-Te and Naha-Te lie in the basic movements and method of breathing (Nagamine, 1998). Shuri-Te systems emphasize natural movement. For instance, the movements of the feet are in a straight line when a step is taken forward or backward. Speed and proper timing is essential in the training for kicking, punching, and striking. Breathing is controlled naturally during training and no artificial breath training is necessary for the mastery of Shuri-Te. In contrast, steady, rooted movements characterize Naha-Te. Unlike the movements in Shuri-Te, the feet travel on a crescent-shaped line. In Naha-Te kata, there is a rhythmic, but artificial, method of breathing in accordance with each movement. Beneath these surface differences, both the methods and aims of all Okinawan karate are one and the same. Their purpose was practical self-defense and effective martial discipline.

Okinawa-Te continued to be practiced in relative secret up until the time when Okinawa was officially recognized under the sovereignty of Japan following the end of the Satsuma rule in 1875. The open practice and eventual popularity of Okinawan karate blossomed in 1901 when the Commissioner of Education, Shintaro Ogawa, recommended that it be included in the physical education of the first middle school of Okinawa. Once it was included into the school systems, its use and popularity became widespread. While the need for a true jitsu (art or technique) had somewhat declined by the advent of the 20th century, karate's value as a character-building and health-promoting martial art was recognized, and it was soon being taught in many of Okinawa's schools. The first karate master to teach in Okinawa's schools was Anko Itosu. He was soon followed by a number of others, including Chojun Miyagi, Kenwa Mabuni, and Gichin Funakoshi.

Over the course of the last 100 years, what was previously known as Naha-Te (Shorei-Ryu) has been divided into several popular styles. Two of the most popular are Goju-ryu and Uechi-ryu (originating from the Chinese art Pangai-Noon). Similary, Shuri-Te (Shorin-Ryu) was also divided into several styles (Kobayashi, Matsubayashi, Shobayashi, Matsumura Orthodox or Saito, and Shorinji).

As tradition tells us, Okinawan Te continued to develop over the years, primarily in three Okinawan cities: Shuri, Naha and Tomari. Each of these towns was a center to a different sect of society: kings and nobles, merchants and business people, and farmers and fishermen, respectively. For this reason, different forms of self-defense developed within each city and subsequently became known as Shuri-Te, Naha-Te and Tomari-Te. Collectively, they constituted Okinawa-Te or Tode (also To-te). Gradually, Te was divided into two main groups: Shorin-ryu, which developed around Shuri and Tomari systems, and Shorei-ryu, which originated from the Naha area. It is important to note, however, that the towns of Shuri, Tomari, Naha are only a few miles apart, and that the differences between their arts were essentially ones of emphasis, not of kind (Bishop, 1994). Furthermore, it has been posited that early masters in these respective areas likely shared information and techniques with each other.

The differences between Shuri-Te and Naha-Te lie in the basic movements and method of breathing (Nagamine, 1998). Shuri-Te systems emphasize natural movement. For instance, the movements of the feet are in a straight line when a step is taken forward or backward. Speed and proper timing is essential in the training for kicking, punching, and striking. Breathing is controlled naturally during training and no artificial breath training is necessary for the mastery of Shuri-Te. In contrast, steady, rooted movements characterize Naha-Te. Unlike the movements in Shuri-Te, the feet travel on a crescent-shaped line. In Naha-Te kata, there is a rhythmic, but artificial, method of breathing in accordance with each movement. Beneath these surface differences, both the methods and aims of all Okinawan karate are one and the same. Their purpose was practical self-defense and effective martial discipline.

Okinawa-Te continued to be practiced in relative secret up until the time when Okinawa was officially recognized under the sovereignty of Japan following the end of the Satsuma rule in 1875. The open practice and eventual popularity of Okinawan karate blossomed in 1901 when the Commissioner of Education, Shintaro Ogawa, recommended that it be included in the physical education of the first middle school of Okinawa. Once it was included into the school systems, its use and popularity became widespread. While the need for a true jitsu (art or technique) had somewhat declined by the advent of the 20th century, karate's value as a character-building and health-promoting martial art was recognized, and it was soon being taught in many of Okinawa's schools. The first karate master to teach in Okinawa's schools was Anko Itosu. He was soon followed by a number of others, including Chojun Miyagi, Kenwa Mabuni, and Gichin Funakoshi.

Over the course of the last 100 years, what was previously known as Naha-Te (Shorei-Ryu) has been divided into several popular styles. Two of the most popular are Goju-ryu and Uechi-ryu (originating from the Chinese art Pangai-Noon). Similary, Shuri-Te (Shorin-Ryu) was also divided into several styles (Kobayashi, Matsubayashi, Shobayashi, Matsumura Orthodox or Saito, and Shorinji).

Early Okinawa Te Masters

TAKAHARA, Peichin (1683-1760) was revered as a great warrior and is said to have been the first to explain the aspects or principles of the word do ("way") as it is referenced in karate-do. The first of these principles is known as ijo, or the way of humility, compassion, and love. The second is katsu, which refers to the understanding or knowledge of the techniques and kata associated with karate, and lastly, fo or the intensity of commitment and dedication to the art that is required in combat. These concepts have been translated as part of the karateka’s (practitioner) responsibility to himself and others. Takahara is most commonly known as the first teacher of Sakugawa Kanga "Tode" who is considered by most to be the "father of Okinawan karate."

Takahara, Peichin was born in the village of Akata Cho in Southern Shuri on the island of Okinawa in the year of 1683. He was of the upper class in Okinawan feudal society. One would then assume that he would be well educated as well as traveled. He was known as an astronomer and map maker. His maps of Okinawa and the Ryukyu Islands were used in 1797 in Japan's plans to prevent further European intrusions into the region. The Ryukyus were looked upon as the first lines of defense from the south.

Takahara, Peichin was born in the village of Akata Cho in Southern Shuri on the island of Okinawa in the year of 1683. He was of the upper class in Okinawan feudal society. One would then assume that he would be well educated as well as traveled. He was known as an astronomer and map maker. His maps of Okinawa and the Ryukyu Islands were used in 1797 in Japan's plans to prevent further European intrusions into the region. The Ryukyus were looked upon as the first lines of defense from the south.

KUSANKU, (AKA: Kung Syanag, Koso Kun, Kong Su Kung) was a Chinese diplomatic title. This emissary was a military attaché, who traveled to Okinawa, as documented in 1761 and provided a demonstration of his fighting art. It is believed that he was trained in Chinese kempo. He instructed "Tode" after the death of Takahara, Sakugawa’s first instructor. Kusanku’s name is associated with several katas among the Shorin-Ryu systems.

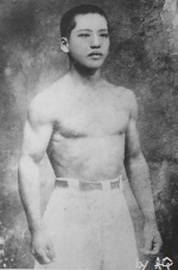

SAKUGAWA, Kanga (1733-1815) was known as "Tode" meaning “karate.” This nickname was given to him by his eminent instructor Peichin Takahara. Known as the "father of Okinawan karate," Sakugawa traveled to China to study the fighting arts. He was born on March 5th of 1733 in Shuri. During his lifetime he was known for combining the Chinese art of ch’uan fa and the Okinawan art of tode ("Chinese hand or empty hand"), forming Okinawa-Te ("Okinawa hand") which would become the foundation for Shuri-Te. He passed down the Kusanku kata, which is said to be one of Okinawa’s oldest katas. Furthermore, he developed a bo kata, Sakugawa no Kon. The image to the left of the text is believed to possibly be Sakugawa's grandson while the drawing below is believed to be the likeness of Kanga himself.

After Sakugawa, the record of transmission becomes blurred. We know the names of three masters who came between Sakugawa and the individual that most Okinawan karate systems trace their lineages from, Matsumura “Bushi” Hohan or Sokon of Shuri Te. However, sometime between the death of Sakugawa and the rise of Shuri-Te, Mayamoto Urazoe, Suekata Chogun, and Chyan Makabe trained with Sakugawa and passed on their knowledge to others. They trained several students, including Sakiyama, of whom little known. He in turn passed on his knowledge to his student, Tomigusuku.

Unknown Chinese teachers were also passing on the fighting arts to Okinawans at this time. For the first time, accounts of masters known largely by their name alone appear, including Gusukuma, teacher of Azato, Kanagusuku, Oyatomari, Yamada, Matsumura, Nakazato, and Toguchi.

Unknown Chinese teachers were also passing on the fighting arts to Okinawans at this time. For the first time, accounts of masters known largely by their name alone appear, including Gusukuma, teacher of Azato, Kanagusuku, Oyatomari, Yamada, Matsumura, Nakazato, and Toguchi.

Kosaku Matsumora was born on the 18th of March 1829, in Tomari village, on Okinawa Island. At the age of 15, when in those days boys began to be treated as adults, he started to learn karate from Master Teruya of Tomari. The young Matsumora became one of Master Teruya's main students, even though he had many followers. Another well-known student of Master Teruya was Kokan Oyadomari, whose name is still synonymous with 'Tomari-te'. Master Teruya taught katas that were only practiced in Tomari, namely "Rohai", "Wanshu" and "Wankan" (sometimes known as "Okan"). He also placed a great deal of emphasis on good behavior, citing "Karate-ni-Sente-Nashi" ("there is no first attack in karate").

He had several students including Choki Motobu, who became renowned for his great fighting skill. Master Motobu was reputed to have learned only Naifanchi (Naihanchi Shodan) kata from Master Matsumora, but this is not true, although he did like the kata and so perhaps practiced it more than others. Another Kata inherited from Master Matsumora is "Matsumora-no-Bassai" (sometimes known as "Tomari-Bassai"). Technically, "Matsumora-no-Bassai" and "Oyadomari-no-Passai" are very similar as both probably come from the same origin. Chotoku Kyan learned "Chinto" from Master Matsumora, and subsequently passed it on to Shoshin Nagamine, founder of Matsubayashi-ryu (Shorin-ryu). Master Matsumora died on 7th November 1898.

He had several students including Choki Motobu, who became renowned for his great fighting skill. Master Motobu was reputed to have learned only Naifanchi (Naihanchi Shodan) kata from Master Matsumora, but this is not true, although he did like the kata and so perhaps practiced it more than others. Another Kata inherited from Master Matsumora is "Matsumora-no-Bassai" (sometimes known as "Tomari-Bassai"). Technically, "Matsumora-no-Bassai" and "Oyadomari-no-Passai" are very similar as both probably come from the same origin. Chotoku Kyan learned "Chinto" from Master Matsumora, and subsequently passed it on to Shoshin Nagamine, founder of Matsubayashi-ryu (Shorin-ryu). Master Matsumora died on 7th November 1898.

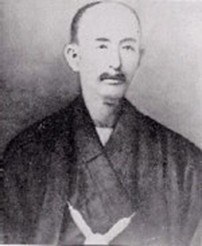

MATSUMURA, Sokon (1809-1893) was born in 1809 in Shuri-Yamakawa village, Okinawa. His Chinese name was Bu Seitatsu. It is believed that he was trained by Sakugawa who agreed to train him in order to fulfill a promise made to Matsumura’s aging father. Matsumura was famous for his intellect and courage as a result of his hard training. He was the chief bodyguard for the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth kings of the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa). Matsumura was twice sent to Fukien, China, and mainland Satsuma (now known as Kagoshima, Japan) as an envoy of the Ryukyuan king. In China, he was allowed to learn the Chinese martial arts, and in Satsuma, he was instructed in the martial arts by Ishuin Yashichiro. This fact was recorded in his family history. While he traced his lineage to Sakugawa through Mayamoto, Urazoe, and Chyan, he also traveled to China to study Go no Kempo (Hard Fist way) or Ch'uan Fa (Fist way).

He left behind the oldest empty hand kata still used by Shorin-ryu, Chinto. The legend goes that he was undefeated as a fighter until he tried to capture a shipwrecked Chinese sailor, who defeated him and escaped. After hunting down the Chinese man, Matsumura begged him to teach his fighting method. To honor this sailor, he used his name, Chinto, and devised a kata of his techniques.

It has been recorded that Matsumura passed on several teachings related to literature and warriorship. Matsumura concluded that both Confucian and Budo teachings should be incorporated into a practitioner’s daily training regiment. Matsumura learned his form of "Te" while in China studying under Wai Shiu Zan. Among his students were Towada, Ishimine, Sakahara, Kenjo, Chinen, Kanagi, Yamanoe, Soe, Kuwasawa, (Anko Itotsu) Yasuzato Yasutsune, and Kuwae (his last formal student). All of these outstanding martial artists came from wealthy families.

Matsumura was the Ryukyuan King's bodyguard up until his death at age 85. There are many tales about his exploits and it is impossible to assess the historicity of the details. In one such incident, Matsumura was pitted to fight another Okinawan Bushi, Kushiguawa Uehara. The fight was to take place in front of the king to determine who would be the chief bodyguard. Both men only threw one punch, with Matsumura winning by skillfully punching Bushi Kushiguawa's punching hand and breaking it.

The most famous story concerning Matsumura involved him fighting a large bull. The Ryukyuan king had always wanted to know whether a man could fight and win against a bull, but he also wanted to see how well Matsumura Sensei could handle himself in a life or death confrontation. When the king gave Matsumura the challenge, he could not refuse because he was the king's chief bodyguard. The other Okinawan Bushi advised him that he would be killed if he took up the challenge. They stated that it would be much wiser for him to step down rather than be needlessly killed.

Matsumura accepted the challenge, and the king then ordered fifteen men to construct a special bull-fighting ring for the fight. The news spread throughout all of Okinawa that the great Matsumura would fight the king's favorite fighting bull. In turn, Matsumura asked the king for three weeks to prepare for the match. The king gave his permission and Matsumura began his preparations to ensure his win and his survival. The next day, Matsumura took a short bamboo spear and went to the stables where the bull was corralled. He told the keeper of the stable that he needed to be alone with the bull in order to make peace with it so that the bull's spirit would not haunt him after he killed it. The keeper honored Matsumura's wish and left. Matsumura then used his cloak to give the bull his scent and then poked its privates with the bamboo spear. The bull became very angry, but could not get at Matsumura because of the strong corral. He continued to terrorize the bull every day for three weeks until the mere sight of Matsumura caused the bull to cry with fright.

On the day of the fight, Matsumura wore his oldest and dirtiest fighting clothes that had not been washed. The dirty clothes carried his scent and his hopes for survival. The bull ring had been situated on the beach and Matsumura arrived at the appointed hour. By then, almost all of Okinawa was there to watch the Bushi meet his match in the king's favorite fighting bull. The Bushi approached the bull ring carrying his favorite bamboo fighting fan and nothing else.

As Matsumura entered the bull ring, the bull was released. The bull began hitting the sides of the ring until it noticed that it was not alone. Matsumura showed no fear and walked slowly toward the animal. As the bull turned to meet him, it immediately recognized Matsumura' s scent and what appeared to be a bamboo spear. The bull turned and ran, giving a loud cry. The king, upon seeing this, said it was truly so, that Matsumura was the greatest of all Bushi.

"Bushi" ("Warrior") is credited for making the most singular contribution, katas, to the development of Okinawan karate. The Shuri-Te system of katas that are still practiced today in the Kobayashi Shorin-Ryu system are Naihanchi (1-3), Passai Dai, Chinto and Gojushiho.

He left behind the oldest empty hand kata still used by Shorin-ryu, Chinto. The legend goes that he was undefeated as a fighter until he tried to capture a shipwrecked Chinese sailor, who defeated him and escaped. After hunting down the Chinese man, Matsumura begged him to teach his fighting method. To honor this sailor, he used his name, Chinto, and devised a kata of his techniques.

It has been recorded that Matsumura passed on several teachings related to literature and warriorship. Matsumura concluded that both Confucian and Budo teachings should be incorporated into a practitioner’s daily training regiment. Matsumura learned his form of "Te" while in China studying under Wai Shiu Zan. Among his students were Towada, Ishimine, Sakahara, Kenjo, Chinen, Kanagi, Yamanoe, Soe, Kuwasawa, (Anko Itotsu) Yasuzato Yasutsune, and Kuwae (his last formal student). All of these outstanding martial artists came from wealthy families.

Matsumura was the Ryukyuan King's bodyguard up until his death at age 85. There are many tales about his exploits and it is impossible to assess the historicity of the details. In one such incident, Matsumura was pitted to fight another Okinawan Bushi, Kushiguawa Uehara. The fight was to take place in front of the king to determine who would be the chief bodyguard. Both men only threw one punch, with Matsumura winning by skillfully punching Bushi Kushiguawa's punching hand and breaking it.

The most famous story concerning Matsumura involved him fighting a large bull. The Ryukyuan king had always wanted to know whether a man could fight and win against a bull, but he also wanted to see how well Matsumura Sensei could handle himself in a life or death confrontation. When the king gave Matsumura the challenge, he could not refuse because he was the king's chief bodyguard. The other Okinawan Bushi advised him that he would be killed if he took up the challenge. They stated that it would be much wiser for him to step down rather than be needlessly killed.

Matsumura accepted the challenge, and the king then ordered fifteen men to construct a special bull-fighting ring for the fight. The news spread throughout all of Okinawa that the great Matsumura would fight the king's favorite fighting bull. In turn, Matsumura asked the king for three weeks to prepare for the match. The king gave his permission and Matsumura began his preparations to ensure his win and his survival. The next day, Matsumura took a short bamboo spear and went to the stables where the bull was corralled. He told the keeper of the stable that he needed to be alone with the bull in order to make peace with it so that the bull's spirit would not haunt him after he killed it. The keeper honored Matsumura's wish and left. Matsumura then used his cloak to give the bull his scent and then poked its privates with the bamboo spear. The bull became very angry, but could not get at Matsumura because of the strong corral. He continued to terrorize the bull every day for three weeks until the mere sight of Matsumura caused the bull to cry with fright.

On the day of the fight, Matsumura wore his oldest and dirtiest fighting clothes that had not been washed. The dirty clothes carried his scent and his hopes for survival. The bull ring had been situated on the beach and Matsumura arrived at the appointed hour. By then, almost all of Okinawa was there to watch the Bushi meet his match in the king's favorite fighting bull. The Bushi approached the bull ring carrying his favorite bamboo fighting fan and nothing else.

As Matsumura entered the bull ring, the bull was released. The bull began hitting the sides of the ring until it noticed that it was not alone. Matsumura showed no fear and walked slowly toward the animal. As the bull turned to meet him, it immediately recognized Matsumura' s scent and what appeared to be a bamboo spear. The bull turned and ran, giving a loud cry. The king, upon seeing this, said it was truly so, that Matsumura was the greatest of all Bushi.

"Bushi" ("Warrior") is credited for making the most singular contribution, katas, to the development of Okinawan karate. The Shuri-Te system of katas that are still practiced today in the Kobayashi Shorin-Ryu system are Naihanchi (1-3), Passai Dai, Chinto and Gojushiho.

ITOSU, Yasutsune (1830-1915)

Itosu was the son of a Tonichi, one of the two highest classes of the Okinawan society. He was born in 1830, in the town of Azato in the Shuri-Yamakawa village, Okinawa. He began studying "Shuri-Te" under Matsumura Sokon at a very young age and was literate enough to be named as the official clerk of the Shuri government. He was furthermore adviser to the Okinawan King in military subjects. He became an expert in horse riding, kendo, and archery. Itosu was also a student of the aforementioned Master Gusukuma and Kosaku Matsumora (Tomari-Te).

Azato, as he was commonly known, maintained a very complete registry of all the martial artists of the island, in these he would detail their abilities and defects. He used to say "Know yourself and your enemy: this is the secret key of strategy." During his lifetime he was defied by Yorin Kanna, the most famous sword trainee of Okinawa, and even though Azato was an expert in Jigen-kenjutsu, he confronted his adversary unarmed. Kanna was known not only for his education but also for his enormous strength. He lacked neither courage nor fighting spirit. He attacked Azato once and again and each time Azato would throw him almost without effort. Azato took the sword out of its trajectory and immobilized Kanna.

Itosu (Itotsu) or Azato was given the name "Anko or Ankoh" ("Iron Horse") because of his proficiency at the Naihanchi stance. He is credited for creating and introducing the Pinans ("Peaceful Mind") I-V Katas to the Okinawan public schools in 1901. He is also credited for Kusanku Sho and Passai Sho. Some of the most important modern day instructors that trained directly under him were: Chibana, Chosin; Funakoshi, Gichin; Kyan, Chotoku; Mabuni, Kenwa, Kanken Toyama, Kentsu Yabu, and Shinpan Gusukuma to name just a few.

When Karate became part of the physical education training at the Shuri Elementary School in 1901, Itosu Sensei was its first instructor. This was the first step for the popularization of modern Okinawan Karate. Between 1905 and 1915, Itosu Sensei was a part-time Karate instructor at the Okinawan Dai Ichi High School. He devoted his entire life to the spread of Shuri style Karate and ended his 85 year long life in 1915. The following are the teachings of Itosu Sensei:

Itosu was the son of a Tonichi, one of the two highest classes of the Okinawan society. He was born in 1830, in the town of Azato in the Shuri-Yamakawa village, Okinawa. He began studying "Shuri-Te" under Matsumura Sokon at a very young age and was literate enough to be named as the official clerk of the Shuri government. He was furthermore adviser to the Okinawan King in military subjects. He became an expert in horse riding, kendo, and archery. Itosu was also a student of the aforementioned Master Gusukuma and Kosaku Matsumora (Tomari-Te).

Azato, as he was commonly known, maintained a very complete registry of all the martial artists of the island, in these he would detail their abilities and defects. He used to say "Know yourself and your enemy: this is the secret key of strategy." During his lifetime he was defied by Yorin Kanna, the most famous sword trainee of Okinawa, and even though Azato was an expert in Jigen-kenjutsu, he confronted his adversary unarmed. Kanna was known not only for his education but also for his enormous strength. He lacked neither courage nor fighting spirit. He attacked Azato once and again and each time Azato would throw him almost without effort. Azato took the sword out of its trajectory and immobilized Kanna.

Itosu (Itotsu) or Azato was given the name "Anko or Ankoh" ("Iron Horse") because of his proficiency at the Naihanchi stance. He is credited for creating and introducing the Pinans ("Peaceful Mind") I-V Katas to the Okinawan public schools in 1901. He is also credited for Kusanku Sho and Passai Sho. Some of the most important modern day instructors that trained directly under him were: Chibana, Chosin; Funakoshi, Gichin; Kyan, Chotoku; Mabuni, Kenwa, Kanken Toyama, Kentsu Yabu, and Shinpan Gusukuma to name just a few.

When Karate became part of the physical education training at the Shuri Elementary School in 1901, Itosu Sensei was its first instructor. This was the first step for the popularization of modern Okinawan Karate. Between 1905 and 1915, Itosu Sensei was a part-time Karate instructor at the Okinawan Dai Ichi High School. He devoted his entire life to the spread of Shuri style Karate and ended his 85 year long life in 1915. The following are the teachings of Itosu Sensei:

- Karate training should not be used for your own interest, but for the protection of your parents, and it is never to be used to hurt anyone.

- Karate training is to be used to make the muscles and bones of the body as hard as a rock and to make the arms and legs as sharp as spears, hence it is so practical that it will help our military society in times to come. The First Duke of Wellington said when he defeated Napoleon I, "Our victory today was attained in our schoolyards."

- Karate cannot be mastered in a short period of time. One to two hours of hard and correct training every day for three or four years will help put you on the right road to understanding Karate and eventually mastering it.

- Karate requires such strong hands and feet that you should train by striking makiwara (striking post) one to two hundred times each day.

- Karate students should train with their limbs straight up, the lungs wide open, the shoulders down and the feet firmly on the ground.

- Karate form (kata) is a training method where meaning and analysis is of the utmost importance.

- Karate form (kata) must also be analyzed by the student to determine its use-whether it is to be used for physical or practical training. Karate training must be as intensive as if one is actually on a battlefield.

- Karate training must be systematic and correct so as to develop one's physical strength.

- Karate experts have lived longer because training develops the muscles and the bones. It also helps the digestive organs and improves the circulation of the blood. Therefore, Karate training should be offered in physical education courses beginning in the elementary school and up.

MATSUMURA, Nabe, was the grandson of Matsumura Hohan (Sokon), and, according to family tradition, he received all the secret techniques and knowledge of his grandfather. The chief instructor of this style (now called the Matsumura Orthodox system of Shorin-ryu) is Soken Hohan, the nephew of Matsumura Nabe. While this system teaches the traditional basic and advanced kata, it also makes use of the Hukutsuru or White Crane forms. Miraculous ability is said to derive from proper practice of White Crane technique, such as the ability to stand or even fight on a small board in rough water. Great emphasis is also placed on Kobujitsu (Weapons Art) in this style.

HIGAONNA, Kanryo (1853 – 1916) was born in Naha. Higaonna learned Chinese Kempo at an early age training in Foochou China with Ryu Ryu Ko and others. He would go on to be a catalyst for what became Naha-Te and what his student, Miyagi Chojun, would later call Goju-Ryu. Higaonna and his lineage is discussed further under the section entitled Naha-Te and Goju-Ryu.

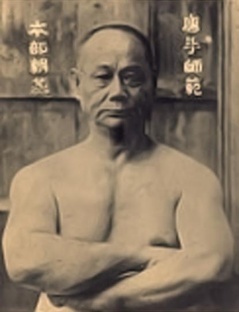

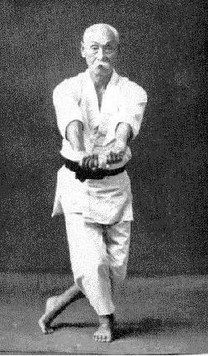

MOTOBU, Choki, (1871-1944) was a fascinating man whose exploits became a source of almost legendary stories and whose fighting instructions influenced a number of the top contemporary masters. He was the third son of an Okinawan lord in Shuri. Being third born meant that he was not able to learn his own family’s fighting system (taught to the first born only). As a result he attempted to train himself. He was given the nickname “Saru,” meaning monkey, due to his exceptional leaping ability. He found formal instruction first under Sokon Matsumura and Kosuku Matsumora, and then later Motobu also studied under Yasutsune Itosu.

His influence and presence in the annals of Shuri-Te’s development reappears throughout the history of the style with connections to many Okinawan practitioners. Because of the deadly nature of the underground karate systems, students flocked to those teachers who demonstrated the ability and the techniques that had been demonstrated to defeat the enemy. In addition, the nature of the conflict opened the doors for cooperation between various schools and instructors – provided they were Okinawan, of course.

Motobu also studied with Tong Gee Hsiang in the Chinese settlement of Kume Mura in Okinawa during the early part of the 1900s. The Chinese settlement existed under of sort a diplomatic immunity in spite of the Japanese occupation. Hsiang had learned Hsing-Yi kempo from his uncle, Shang Tsau Hsiang. It has been suggested that the elder Hsiang had combined the internal Chinese systems of Hsing-Yi and Pa-Kua with the external systems of Shaolin kung fu and others. Some written accounts also state that Tong Gee Hsiang was also a master of Shuri-Te.

As legend has it, Motobu entered a fighting contest in 1921 against a professional boxing champion. His rapid and decisive victory earned him the respect of many would-be karate students. He continued his training under Kentsu Yabu. Choki Motobu’s family style (Motobu-Ryu) was carried on through his eldest brother Choyu Motobu and was recently passed through Seikichi Uehara who coined the name in recognition of his teacher and the Motobu family. Choki Motobu had many notable students including: Konishi, Yamada, Ninomiya, Nakama, Uejima (Kushin-Ryu), Ohtsuka (Wado-Ryu), and Nagamine (Matsubayashi Shorin-Ryu).

His influence and presence in the annals of Shuri-Te’s development reappears throughout the history of the style with connections to many Okinawan practitioners. Because of the deadly nature of the underground karate systems, students flocked to those teachers who demonstrated the ability and the techniques that had been demonstrated to defeat the enemy. In addition, the nature of the conflict opened the doors for cooperation between various schools and instructors – provided they were Okinawan, of course.

Motobu also studied with Tong Gee Hsiang in the Chinese settlement of Kume Mura in Okinawa during the early part of the 1900s. The Chinese settlement existed under of sort a diplomatic immunity in spite of the Japanese occupation. Hsiang had learned Hsing-Yi kempo from his uncle, Shang Tsau Hsiang. It has been suggested that the elder Hsiang had combined the internal Chinese systems of Hsing-Yi and Pa-Kua with the external systems of Shaolin kung fu and others. Some written accounts also state that Tong Gee Hsiang was also a master of Shuri-Te.

As legend has it, Motobu entered a fighting contest in 1921 against a professional boxing champion. His rapid and decisive victory earned him the respect of many would-be karate students. He continued his training under Kentsu Yabu. Choki Motobu’s family style (Motobu-Ryu) was carried on through his eldest brother Choyu Motobu and was recently passed through Seikichi Uehara who coined the name in recognition of his teacher and the Motobu family. Choki Motobu had many notable students including: Konishi, Yamada, Ninomiya, Nakama, Uejima (Kushin-Ryu), Ohtsuka (Wado-Ryu), and Nagamine (Matsubayashi Shorin-Ryu).

YABU, Kentsu (1863 – 1937) Yabu began to train in Matsumura Hohan's dojo mainly under the tutelage of Itosu, the master's senior student. Yabu took over the system upon Itotsu’s death until age and injuries forced him to retire. Conflicting stories exist about Yabu, some authorities saying he was gentle and a good teacher, and some saying he enjoyed Shinken Shobu or Shobishi Kumite (Fight to the Death or Knockout). Legend says Yabu killed over 60 men in hand-to-hand combat, and that he even defeated the famous giant Okinawan Shorei-ryu master Motobu Choku. All legends aside, Yabu left two well remembered students, Taira Kenshin and Toyama Kanken.

Yabu, known as “the sergeant” taught in Hawaii in 1927. One of his greatest claims to fame as a martial artist was that he defeated the previously unbeatable Choki Motobu in a fight. He left many notable students behind including Chosin Chibana, Kanken Toyama, and Shinpan Gusukuma.

Yabu, known as “the sergeant” taught in Hawaii in 1927. One of his greatest claims to fame as a martial artist was that he defeated the previously unbeatable Choki Motobu in a fight. He left many notable students behind including Chosin Chibana, Kanken Toyama, and Shinpan Gusukuma.

KIYAN, Chotoku (1870 – 1945), born in Shuri to descendants of Okinawan nobility in December 1870. Kiyan's whole life was a struggle against misfortune. But Kiyan Chotoku embodied the true spirit of karate by always fighting to overcome adversity, never complaining about hardship, and exerting all his strength to further the art of karate. Kiyan started his training at an early age (8) with Bushi Matsumura. He was later instructed by Itotsu and Oyadomari. Kiyan's students included Shimabuku (Isshin-ryu), Chibana (Shorin-Ryu), Funakoshi (Shotokan), Nagamine (Matsubayashi Shorin-Ryu), Eizo Shimabuku (Shorinji-Ryu), and Tsuyoshi Chitose (Chito-Ryu).

FUNAKOSHI, Gichin (1868 – 1957) is known today as the father of modern karate. He studied under Itosu as well as under Itosu’s friend, Yasutsune Azato (often confused with the former Azato due to name similarity).

Gichin Funakoshi was born in Shuri, Okinawa in 1868, the same year as Japan's Meiji Restoration. Introduced to karate as a boy, Funakoshi’s early training took place in complete secrecy -- at the time, the Okinawan government had banned the practice of karate. Funakoshi eventually became a schoolteacher, training in karate all the while. During this time, Okinawan karate emerged from its seclusion to become a legally sanctioned martial art. In 1903 he was one of several martial artists that assisted in the incorporation of karate into the physical education curriculum in the Shuri school system. In 1922, the Japanese Ministry of Education held a martial arts demonstration in Tokyo; the Okinawan Department of Education asked Funakoshi to introduce Okinawan karate to Japan.

Funakoshi did not get the chance to return to Okinawa. His demonstration made a powerful impression on the Japanese public; Funakoshi was soon besieged with requests to further demonstrate and teach his art. Eventually, he had enough students to open a modest dojo in a Tokyo dormitory's lecture hall. Local universities began to take an interest in karate, and Funakoshi became a regular instructor at a number of them. The ranks of Funakoshi's students grew.

Recognizing that the karate he practiced had diverged from the Chinese fighting styles, Funakoshi changed the meaning of "karate" from "Chinese hand" to "empty hand." ("Kara" can also mean "empty".) The change was important to Funakoshi: the "empty hand" concept not only reflected the fact that its practitioners used no weapons, it also recalled the Zen process of perfecting oneself and one's art -- by emptying the heart and mind of earthly desire and vanity. Funakoshi also set out to make karate more accessible to the public. He revised and streamlined the components of karate training, especially the kata, to make karate simple enough for everybody -- young and old, men and women.

Karate began to spread throughout Japan. In 1935, Funakoshi's supporters had pooled enough funds to erect the first free-standing karate dojo in Japan. The dojo opened the next year, with a sign over the door bearing the dojo's name: Shoto-kan. ("Kan" means "building." "Shoto" means "pine waves," which describes the sound of the wind rustling through pine trees. Funakoshi, who loved nature, was fond of this murmuring sound -- he considered it a kind of "celestial music." Therefore, he used the name "Shoto" to sign his calligraphy.)

In 1955, the Japan Karate Association was established -- Funakoshi's art had become a full-fledged karate organization. At the time, it was a modest one, with only a few members, a handful of instructors, and Funakoshi, who served as chief instructor. Gichin Funakoshi passed away shortly, on April 26, 1957. Since then, Shotokan students have carried on his spirit and teachings. The result: the JKA now has over 100,000 active karate students and approximately 300 affiliated karate clubs worldwide.

Gichin Funakoshi was born in Shuri, Okinawa in 1868, the same year as Japan's Meiji Restoration. Introduced to karate as a boy, Funakoshi’s early training took place in complete secrecy -- at the time, the Okinawan government had banned the practice of karate. Funakoshi eventually became a schoolteacher, training in karate all the while. During this time, Okinawan karate emerged from its seclusion to become a legally sanctioned martial art. In 1903 he was one of several martial artists that assisted in the incorporation of karate into the physical education curriculum in the Shuri school system. In 1922, the Japanese Ministry of Education held a martial arts demonstration in Tokyo; the Okinawan Department of Education asked Funakoshi to introduce Okinawan karate to Japan.

Funakoshi did not get the chance to return to Okinawa. His demonstration made a powerful impression on the Japanese public; Funakoshi was soon besieged with requests to further demonstrate and teach his art. Eventually, he had enough students to open a modest dojo in a Tokyo dormitory's lecture hall. Local universities began to take an interest in karate, and Funakoshi became a regular instructor at a number of them. The ranks of Funakoshi's students grew.

Recognizing that the karate he practiced had diverged from the Chinese fighting styles, Funakoshi changed the meaning of "karate" from "Chinese hand" to "empty hand." ("Kara" can also mean "empty".) The change was important to Funakoshi: the "empty hand" concept not only reflected the fact that its practitioners used no weapons, it also recalled the Zen process of perfecting oneself and one's art -- by emptying the heart and mind of earthly desire and vanity. Funakoshi also set out to make karate more accessible to the public. He revised and streamlined the components of karate training, especially the kata, to make karate simple enough for everybody -- young and old, men and women.

Karate began to spread throughout Japan. In 1935, Funakoshi's supporters had pooled enough funds to erect the first free-standing karate dojo in Japan. The dojo opened the next year, with a sign over the door bearing the dojo's name: Shoto-kan. ("Kan" means "building." "Shoto" means "pine waves," which describes the sound of the wind rustling through pine trees. Funakoshi, who loved nature, was fond of this murmuring sound -- he considered it a kind of "celestial music." Therefore, he used the name "Shoto" to sign his calligraphy.)

In 1955, the Japan Karate Association was established -- Funakoshi's art had become a full-fledged karate organization. At the time, it was a modest one, with only a few members, a handful of instructors, and Funakoshi, who served as chief instructor. Gichin Funakoshi passed away shortly, on April 26, 1957. Since then, Shotokan students have carried on his spirit and teachings. The result: the JKA now has over 100,000 active karate students and approximately 300 affiliated karate clubs worldwide.

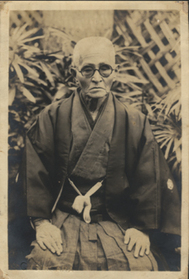

HANASHIRO, Chomo (1869 – 1945) studied Shuri-Te under Matsumura and Itosu. Hanashiro was born in 1869 and at an early age began training with the man many consider to be the greatest of all Tote masters, Matsumura Sokon (1809-1901), well known as "Bushi" Matsumura. Matsumura was quite an old man at the time and Hanashiro was primarily a student of Itosu Anko (1830-1915). Itosu shaped modern karate as much as any other person in history and spearheaded a movement to bring Tote into the Okinawan school system around the turn of the century. Hanashiro remained with Itosu, and acted as an assistant instructor for him up until his death in 1915.

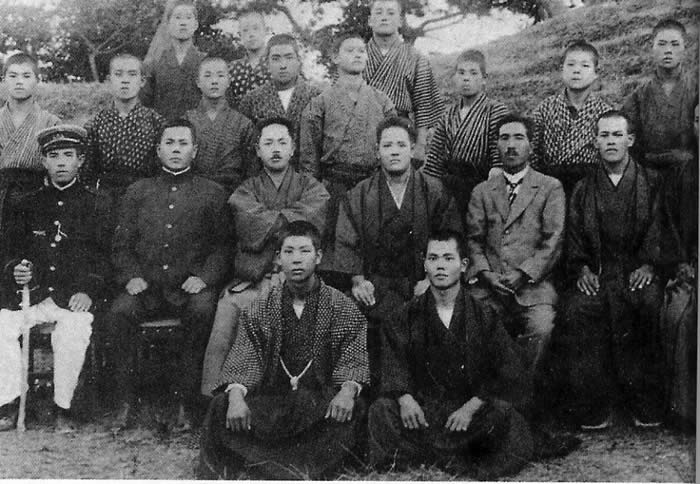

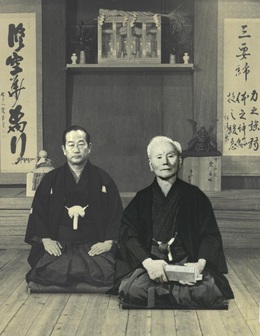

In the 1920's, Hanashiro Chomo was one of the most highly regarded karate masters in Okinawa, despite this, information about him is rare in English language texts. It is difficult to talk about the life of Hanashiro Chomo without also talking about another of Itosu's senior students and assistants, Yabu Kentsu (1863-1937), also originally a student of Matsumura. These two shared many common experiences and have remarkably similar karate careers. Both were noted as having exceptional physiques in the 1891 Japanese army draft's medical exams. They were both pioneers in instructing karate in the school system in the first decade of the 20th century, and also taught Tote in military schools. Both were also present at the famous Oct. 25th, 1936 meeting of Okinawan Masters (see photo below). At this meeting, attended by the greatest masters of the time, the name "karate do" was officially adopted over "Tote Jutsu".

Hanashiro was not only a pioneer in the school system, he pioneered the use of the word "karate". In his August 1905 publication, "Karate Shoshu Hen" ("Karate Kumite"), we can see the first known use of the modern kanji from the original "To-te" (China hand) to the modern "Kara-te" (Empty hand). Hanashiro was one of the primary instructors for an organization formed in the early 1920's in Okinawa called the Ryukyu Tote Kenkyukai (Okinawan Tote Research Club). The organization was meant to continue the teachings of Itosu Anko, Higashionna Kanryo and Aragaki Seisho, the last generation of masters who had died between 1915 and 1918.

Hanashiro Chomo had a few famous students, of particular note are Nakamura Shigeru (1892 or 1895-1969 of Okinawan Kempo), Chitose (1898-1984, founder Chito Ryu), Nakama Chozo (1899-1982, of Kobayashi Ryu), Shimabukuro Zenryo (1904-1969, founder of Seibukan Shorin Ryu) and Kinjo Hiroshi.

In the 1920's, Hanashiro Chomo was one of the most highly regarded karate masters in Okinawa, despite this, information about him is rare in English language texts. It is difficult to talk about the life of Hanashiro Chomo without also talking about another of Itosu's senior students and assistants, Yabu Kentsu (1863-1937), also originally a student of Matsumura. These two shared many common experiences and have remarkably similar karate careers. Both were noted as having exceptional physiques in the 1891 Japanese army draft's medical exams. They were both pioneers in instructing karate in the school system in the first decade of the 20th century, and also taught Tote in military schools. Both were also present at the famous Oct. 25th, 1936 meeting of Okinawan Masters (see photo below). At this meeting, attended by the greatest masters of the time, the name "karate do" was officially adopted over "Tote Jutsu".

Hanashiro was not only a pioneer in the school system, he pioneered the use of the word "karate". In his August 1905 publication, "Karate Shoshu Hen" ("Karate Kumite"), we can see the first known use of the modern kanji from the original "To-te" (China hand) to the modern "Kara-te" (Empty hand). Hanashiro was one of the primary instructors for an organization formed in the early 1920's in Okinawa called the Ryukyu Tote Kenkyukai (Okinawan Tote Research Club). The organization was meant to continue the teachings of Itosu Anko, Higashionna Kanryo and Aragaki Seisho, the last generation of masters who had died between 1915 and 1918.

Hanashiro Chomo had a few famous students, of particular note are Nakamura Shigeru (1892 or 1895-1969 of Okinawan Kempo), Chitose (1898-1984, founder Chito Ryu), Nakama Chozo (1899-1982, of Kobayashi Ryu), Shimabukuro Zenryo (1904-1969, founder of Seibukan Shorin Ryu) and Kinjo Hiroshi.

Arakaki Ankichi (1899-1927)

Born in Shuri, Ankichi trained under both Shinpan Gusukuma (Shinpan Shiroma, 1890-1954), Chomo Hanashiro, and Chibana Chosin. Although dying prematurely, he was instrumental in the training of Nagamine Shoshin of Matsubayashi Shorinryu.

Born in Shuri, Ankichi trained under both Shinpan Gusukuma (Shinpan Shiroma, 1890-1954), Chomo Hanashiro, and Chibana Chosin. Although dying prematurely, he was instrumental in the training of Nagamine Shoshin of Matsubayashi Shorinryu.

Yoshimura Choki (1866-1945)

Choki studied okinawa karate under Matsumura Soken and kanryo Higaonna

Choki studied okinawa karate under Matsumura Soken and kanryo Higaonna

Kyoda Juhatsu (1887-1968)

Juhatsu initially began his training in Naha te under Hanashiro until his death in 1915, and then trained with Chojun Miyagi. After receiving his kyoshi license in 1934 he founded his own system, toon ryu (Higaonna style - named for his first teacher).

Juhatsu initially began his training in Naha te under Hanashiro until his death in 1915, and then trained with Chojun Miyagi. After receiving his kyoshi license in 1934 he founded his own system, toon ryu (Higaonna style - named for his first teacher).